Purpose & Strategy: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

* [[Product Owner]] | * [[Product Owner]] | ||

* [[Release Strategy]] | |||

* [[Backlog Strategy]] | * [[Backlog Strategy]] | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

# [https://www.ted.com/talks/simon_sinek_how_great_leaders_inspire_action?language=en How Great Leaders Inspire Action] accessed 4 July 2018 | # [https://www.ted.com/talks/simon_sinek_how_great_leaders_inspire_action?language=en How Great Leaders Inspire Action] accessed 4 July 2018 | ||

Revision as of 05:28, 3 December 2018

Purpose and Strategy

Strategic thinking is to consider things at a high level and evaluate the longer ranging impacts from our actions or the actions of others. Tactical thinking by comparison considers the near-term actions and what can be done to achieve the best results right now.

The tendency for most organisations is to only focus on the near term tactical actions, and although mostly successful in the near term, the longer-term impacts can be neglected. Hence, some high-level thinking and positioning of the product or service to consider why it is needed, the potential pitfalls and the far-reaching consequences of introducing the new product or service can help to avoid risk, get the best out of the team and satisfy the customer needs.

Injecting some strategic thinking can correlate to a product’s success and how it is received in the market, and so should be a line of enquiry for any new venture.

Visioning

Having a vision and a sense of purpose can galvanise efforts towards a project, especially if the purpose of the work is to contribute to some socially responsible goal that will benefit others for example.

Most programs of work in practice neglect to have a vision, and instead focus on delivering their features to the market efficiently without any high-level perspective or cohesion to the work. This can result in a product with superfluous features or a disjointed customer experience, as the tactical approach to deliver more features overshadowed the strategic thinking of “why” we wanted the features in the first place, and what impact do these new features have on the overall user experience and the product long term.

A good vision is one that inspires and provokes a “greater than the self” purpose that aligns the teams’ personal values to a product they can believe in and are passionate about.

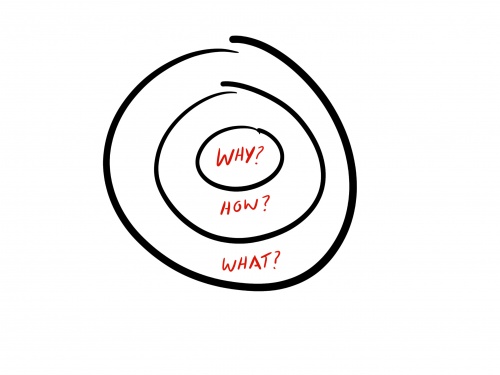

Golden Circle (Simon Sinec)

Simon Sinec presents a model called the Golden Circle[1], which looks to use the following format:

- Why – why will this product revolutionise my experience and why do I need it to achieve my goals?

- How – how will this product help me to achieve my goals?

- What – what is the product and what are the features?

Most organisations tend to market and sell the “what” first and then explain “how” they will work, finally answering the “why” you need it question. Reversing the order to focus on the “why” first can really help to understand the customers’ needs, motivations and their goals that they are trying to satisfy, which leads to a higher awareness and alignment of the purpose behind the product.

As well as using this approach for advertising and marketing, it can also be used to construct a vision statement for the work.

For example:

- We want to combat global warming by reducing carbon emissions of transport, (the “why”.)

- We can achieve this by reducing the number of vehicles on the roads by offering spare seats to paying customers, (the “how”.)

- Our smartphone app called “Spare Share” allows users to sell and rent spare seats in registered vehicles, (the “what”.)

Evolutionary Strategy

Products vs. Projects

In recent times there has been a shift from commissioning projects to create and maintain software programs towards considering them as products and enduring assets of the organisation that should be continuously refined.

Projects tend to:

- be a collection of new features and functionality

- be comparatively large batches of change

- handle large risk all at once

- be funded individually

- use time to market as the focus and have estimated, timelines and milestones to be achieved

- be short lived and tactical in nature to fulfil an immediate need

- be based upon a defined and fixed customer experience

- be implemented by a temporary team that disbands after the project

- be made up of a few large releases, and most projects tend to only release once

- be supported by business as usual (BAU) approaches

Products by comparison, tend to:

- be a continual series of small enhancements and new features

- be small batches of change released more often

- handle small amounts of risk more often

- not be funded, however, the team implementing the changes are funded separately on an annual basis

- use value to market as the focus and estimates tend to no longer be needed

- be strategic long-lived assets of the organisation that are curated and continually refined

- be based upon a constantly evolving customer experience

- be refined by a permanent product team that takes accountability for the product

- be updated with a large number of small releases that tend to be automated where possible

- be primarily developed using business as usual (BAU) approaches

Evolving from a project to a product approach can involve some change in mindset, as the product is considered to be a permanent fixture or asset of the organisation that needs to be constantly curated and refined. This involves changing from facilitating large batches of change, measuring progress towards those changes and managing large amounts of risk at once to setting up a constant stream of rapid releases that implement small changes to refine the asset over time.

The benefits of doing this include:

- smoother flow of changes of the asset

- risk is managed continually

- the customer experience is constantly curated and evaluated

- training materials tend not to be needed as the user begins to be educated and guided with small incremental changes

- funding is team oriented rather than work oriented

- rapid releasing more often allows teams to gain more experience at releasing improving their ability to release faster

- rapid releasing improves the organisation’s use of experiments and customer testing for example

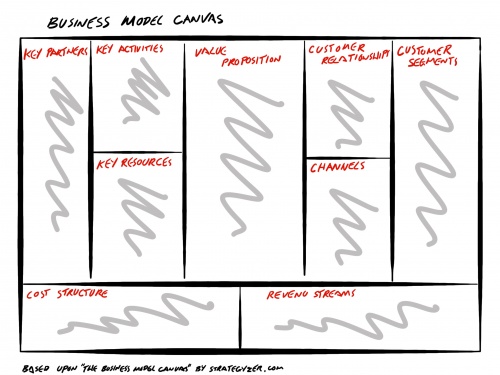

Business Model Canvas

The Business Model Canvas or sometimes referred to as the Learning Canvas has a number of sections designed to match perceived customer needs to organisation capabilities.

They can be used to outline the high-level intentions of the product or service and can be evolved over time as more is known to form an evolving strategy. In the example we have the following components:

- Customer Segments – defining which customer groups the product or service is targeting

- Customer Relationships – what relationships do we have with the customers in order to understand them and try new products and features

- Channels – how can the customers be reached and through which channels

- Key Partners – who are our key partners that can help to provide the new product or service

- Key Activities – what are the key activities that we will need to do to achieve the new product or service

- Key Resources – what resources will we need to provide the new product or service

- Value Proposition – after understanding the customer needs and our capabilities, what is the value proposition for the customer and our organisation

- Cost Structure – what costs do we perceive to provide the new product or service

- Revenue Streams – how do we expect to make revenue from the new product or service

Business Model Canvasses are often used to provide context for new products and features, and can be used as hypotheses to be proved, refined or disproved in an experimental cycle.

See Also

References

- How Great Leaders Inspire Action accessed 4 July 2018